An excerpt from my someday-finished novel, Photorealistic Raccoons.

■

“Cyborg Prophet’s pretty good this month,” Trent said.

“I hate Cyborg Prophet,” Gerry said.

“Why?”

“ ’Cause it’s so boring. The characters do nothin’ but talk about machines and philosophy and stuff.”

“Some comic books prefer to spend their time making you think.”

“I do enough thinking at school.”

Another fine afternoon at Trent’s house. No one else was there. Both Trent’s parents worked, making him the first latchkey kid Gerry had ever known, years before either boy would hear of latchkey kids.

Whenever Gerry would visit, he would hang out in Trent’s bedroom to read comics. Trent stored his collection upright in a long white cardboard box, in alphabetical and chronological order, on his dresser. He would spend a few moments checking out the comics Gerry had brought, which usually featured capes and/or punching on their covers. Then, without a word, Trent would walk to his dresser, remove the lid from the box, set the lid down next to the box, and let Gerry pick out a few titles that usually featured spacesuits and/or punching on their covers.

Trent would slide the comics out of their clear plastic sleeves. (Of course he kept his comics in clear plastic sleeves.) “Treat these with the utmost care,” he would say as he handed Gerry items such as Mindburn #17 (March 1973), or Explorers of New Terra #3 (October 1972), or other full-color pictorial narratives that allegedly might increase in value someday. Trent called them “pictorial narratives.”

After reading each comic book, Gerry would return it to him. Carrying that comic flat in his hands, Trent would walk to his desk and turn on his desk lamp, the quintessential blunt object: twelve inches of brown metal with a heavy, curving, pyramidal base. The lamp had a brown metal shade about a foot-and-a-half long, the longest Gerry had ever seen. A fluorescent bulb under the shade would provide enough light for Trent to inspect the comic minutely, from cover to cover, squinting, his mouth hanging slightly open, as it tended to do when he concentrated on a task of the utmost importance. Sometimes he would tsk-tsk Gerry for, say, leaving a greasy thumbprint on the front cover, or for minutely creasing the lower corner of page seventeen; usually, though, Trent would close his mouth, turn off the lamp, insert the comic into its sleeve, get up, walk to his dresser, bury his treasure once again inside the box, pick up the lid, clamp it down tight, and pat it a few times.

He was the first collector nerd Gerry had ever known, years before either of them would hear of collector nerds—or of nerds, for that matter. Trent certainly looked like a nerd: black-framed glasses, bowl-shaped haircut, acres of pimples, Funny Bunny T-shirt, brown floodpants, dark-brown clodhoppers.

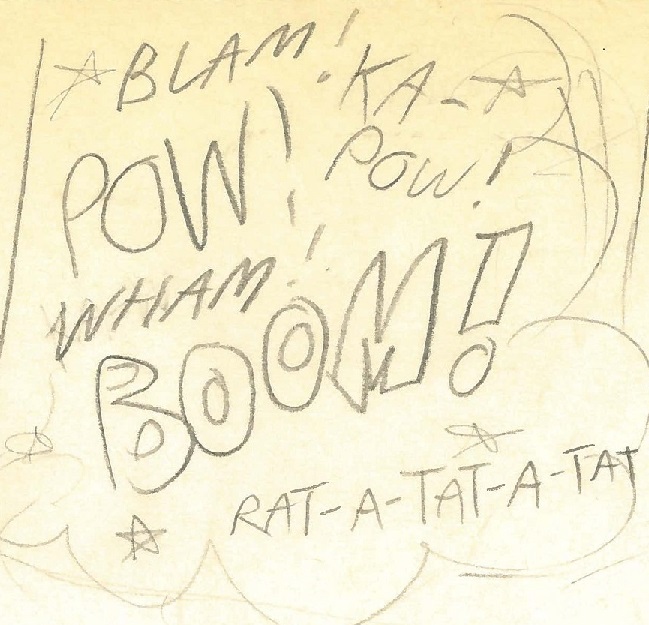

That afternoon, the boys were lying on their stomachs, on the floor, the usual way the boys read comics together. Trent had gotten halfway through Captain Cobalt #14 (July 1973), which Gerry had already read during the previous visit and proclaimed the dullest issue yet, endless exposition instead of the gargoyle showdown that title had promised last month, though of course Trent loved endless exposition (and rivets—lots of rivets in that title, endless rows of them on every mechanical device). Gerry had almost finished something he’d brought from home, The Red Laser #1 (August 1973), one of the best comics he’d read so far that year, about a short, puny, and homely teenager named Mike Morganson, not the most popular guy, who—

“Hmm mmm, mmm hmm mmm mmm.”

“Stop it,” Gerry said.

Trent stopped humming.

—who lives in this big city called Biggs City. One night, he borrows his parents’ car without their permission and goes out driving in the country alone (“I’m sick of everyone hassling me!”) and sees a flying saucer. He gets out of his car for a closer look, and the saucer beams him aboard, and the invisible aliens inside—

“Mmm hmm hmm hmm.”

“I said stop it,” Gerry said.

Trent did.

—the aliens, from a planet called Laseria, tell him, Mike Morganson, that their advanced scientific technology has determined that of all the known lifeforms in existence, he’s the Chosen One, the super-warrior who can protect the universe from the ruthless evildoers who threaten its very existence. (“Me? I’m the Chosen One? You sure it’s not Joe Namath?”) The aliens zap him, Mike Morganson, with a luminous red ray to bring forth the powers he hadn’t known he possessed. He now can transform himself into a tall, handsome, muscular guy who has the strength of a thousand Earth men and can fly at the speed of light and—

“Mmm hmm hmm.”

“I swear, Trent, if you hum one more time, just one more time, I’m gonna beat the livin’ crap out of you. Got it?”

“Uh-huh.”

—and most important, can shoot red lasers out of his hands. So he calls himself the Red Laser (“Good enough name as any”) and wears a tight red costume that covers his entire body, and he—

“Daid skunk, yeah, there’s a daid skunk.”

“Trent!”

“Daid skunk, dead skunk, dead skunk on da road.”

The song “Dead Skunk” by Loudon Wainwright III had been a hit that spring. Gerry had liked that song; well, he used to like it until that moment, when Trent started butchering it. Needless to say, Loudon Wainwright III hadn’t sung the original version tunelessly with a goofball hick accent, an accent Trent would adopt on occasion in a futile effort to amuse people. And those weren’t even the original lyrics.

“Violate da speed limit, hit dat skunk with your car.”

“Will you shut up!”

“P.U., a daid skunnnnnk! Yeah, yeahhhhhhh!”

“That’s it!”

Trent started to stand up, but Gerry tackled him, knocking him onto the carpet and perching atop him.

“I’m sorry,” Trent said, flat on his back. “I won’t do it again.”

Gerry removed Trent’s glasses.

“Please, those cost sixty-three dollars and seventy-eight cents.”

Gerry snapped the glasses in half and tossed them to one side.

“You owe me for those.”

Gerry punched him in the mouth. Another punch in the mouth. Trent looked frightened, displaying an actual emotion for a change. With increasing frenzy, Gerry punched Trent’s face, Trent’s arms, Trent’s chest. At first Trent writhed around, but as the beating progressed, he gradually stopped moving.

Gerry pulled Trent’s hair.

“Auuuugh!” Trent yelped.

“Shut up,” Gerry said, punching him in the mouth yet again. More punches and slaps to the face. More hair-pulling. Several karate chops to the face, neck, and body.

Finally, Gerry grew tired and stopped.

Trent cried, his nose trickling blood, his mouth pouring blood, his eyes squinting due to the lack of corrective lenses.

“Tell on me, and you’re dead,” Trent said in a low voice. “Got it?”

More crying.

Another slap, the most powerful one in recorded history, a slap that actually hurt Gerry’s hand.

“Got it?”

“Yes,” Trent said.

Not saying anything else, his hand still hurting, Gerry picked up his comics from off the floor and went home.

For the rest of the day, he had a sense of impending doom. He thought any minute now, his parents would confront him, his father asking “Did you beat up Trent Deutsch this afternoon?”

“No,” Gerry would reply, “I beat the living crap out of him, ’cause he deserved it. He was bothering me.”

“Well, even if he did deserve it, he’s a retard. You can’t go around beating the living crap out of retards. They’re—well, they’re retards. Which means I gotta beat the living crap out of you now. Don’t worry, it shouldn’t take very long. I have work to do.”

But nothing happened. And when Trent showed up at school the next day, a swollen eye, a swollen lip, a couple bruises on his face, his glasses masking-taped together, he acted as if he didn’t know Gerry, which suited the latter boy just fine, who hoped this development would continue so he, Gerry, could read The Red Laser #2 in peace, if the comics company ever released another issue, and why wouldn’t they? (They never did.)

Copyright © 2025 by David V. Matthews